Nescience: A user-centric state-separation architecture.

Disclaimer: This content is a work in progress. Some components may be updated, changed, or expanded as new research findings become available.

In blockchain applications, privacy settings are typically predefined by developers, leaving users with limited control. This traditional,

one-size-fits-all approach often leads to inefficiencies and potential privacy concerns as it fails to cater to the diverse needs of individual users.

The Nescience state-separation architecture (NSSA) aims to address these issues by shifting privacy control from developers to users. NSSA introduces a flexible,

user-centric approach that allows for customized privacy settings to better meet individual needs. This blog post will delve into the details of NSSA,

including its different execution types, cryptographic foundations, and unique challenges.

NSSA gives users control over their privacy settings by introducing shielded (which creates a layer of privacy for the outputs, and only the necessary details are shared)

and deshielded (which reveal private details, making them publicly visible) execution types in addition to the traditional public and private modes. This flexibility allows

users to customize their privacy settings to match their unique needs, whether they require high levels of confidentiality or more transparency. In NSSA, the system is divided

into two states: public and private. The public state uses an account-based model while the private state employs a UTXO-based (unspent transaction output) model. Private executions within NSSA utilize

UTXO exchanges, ensuring that transaction details remain confidential. The sequencer verifies these exchanges without accessing specific details, enhancing privacy by unlinking

sender and receiver identities. Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) allow users to prove transaction validity without revealing data, maintaining the integrity and confidentiality of

private transactions. UTXOs contain assets such as balances, NFTs, or private storage data, and are stored in plaintext within Sparse Merkle trees (SMTs) in the private state and

as hashes in the public state. This dual-storage approach keeps UTXO details confidential while allowing public verification through hashes, achieving a balance between privacy and transparency.

Implementing NSSA introduces unique challenges, particularly in cryptographic implementation and maintaining the integrity of private executions. These challenges are addressed

through various solutions such as ZKPs, which ensure transaction validity without compromising privacy, and the dual-storage approach, which maintains confidentiality while enabling

public verification. By allowing users to customize their privacy settings, NSSA enhances user experience and promotes wider adoption of private execution platforms. As we move towards

a future where user-empowered privacy control is crucial, NSSA provides a flexible and user-centric solution that meets the diverse needs of blockchain users.

In many existing hybrid execution platforms, privacy settings are predefined by developers, often applying a one-size-fits-all approach that does not accommodate the

diverse privacy needs of users. These platforms blend public and private states, but control over privacy remains with the application developers.

While this approach is straightforward for developers (who bear the responsibility for any potential privacy leaks), it leaves users with no control over their own privacy settings.

This rigidity becomes problematic as user needs evolve over time, or as new regulations necessitate changes to privacy configurations. In such cases,

updates to decentralized applications are required to adjust privacy settings, which can disrupt the user experience and create friction.

NSSA addresses these limitations by introducing a groundbreaking concept: selective privacy. Unlike traditional platforms where privacy

is static and determined by developers, selective privacy empowers users to dynamically choose their own privacy levels based on their unique needs and sensitivity.

This flexibility is critical in a decentralized ecosystem where the diversity of users and use cases demands a more adaptable privacy solution.

In the NSSA model, users have the autonomy to select how they interact with decentralized applications (dapps) by choosing from four types of transaction executions: public,

private, shielded, and deshielded. This model allows users to tailor their privacy settings on a per-transaction basis, selecting the most appropriate execution type for each

specific interaction. For instance, a user concerned about data confidentiality might opt for a fully private transaction while another user, wary of privacy but seeking transparency,

might choose a public execution.

While selective privacy may appear complex, especially for users who are not technically inclined, Nescience mitigates this by allowing the community or developers to

establish best practices and recommended approaches. These guidelines provide users with an informed starting point, and over time, users can adjust their privacy

settings as their preferences and trust in the platform evolve. Importantly, selective privacy gives users the right to alter their privacy level at any point in the future,

ensuring that their privacy settings remain aligned with their needs as they change.

This approach not only empowers users but also facilitates greater adoption of dapps. Users who are skeptical about privacy concerns can initially engage with transparent

transactions and gradually shift towards more private executions as they gain confidence in the system and vice versa for users who start with privacy but later find transparency

beneficial for certain transactions. In this way, selective privacy bridges the gap between privacy and transparency, allowing for an optimal balance to emerge from the community’s

collective preferences.

To liken this to open-source projects: in traditional systems, developers fix privacy rules much like immutable code—users must comply with these fixed settings.

In contrast, with selective privacy, the rules are malleable and shaped by the users’ preferences, enabling the community to find the ideal balance between privacy and efficiency over time.

NSSA is distinct from traditional zero-knowledge (ZK) rollups in several key ways. One of the unique features of NSSA is its public execution type, which does not

require ZKPs or a zero-knowledge virtual machine (zkVM). This provides a significant advantage in terms of scalability and efficiency as users can choose public executions for

transactions that do not require enhanced privacy, avoiding the overhead associated with ZKP generation and verification.

Moreover, NSSA introduces two additional execution types—shielded and deshielded—which further distinguish it from traditional privacy-preserving rollups.

These execution types allow for more nuanced control over privacy, giving users the ability to shield certain aspects of a transaction while deshielding others.

This flexibility sets NSSA apart as a more adaptable and user-centric platform, catering to a wide range of privacy needs without imposing a one-size-fits-all solution.

By combining selective privacy with a flexible execution model, NSSA offers a more robust and adaptable framework for decentralized applications,

ensuring that users maintain control over their privacy while benefiting from the security and efficiency of blockchain technology.

NSSA offers a flexible, privacy-preserving add-on that can be applied to existing dapps.

One of the emerging trends in the blockchain space is that each dapp is expected to have its own rollup for efficiency, and it is estimated that Ethereum could see

the deployment of different rollups in the near future. A key question arises: how many of these rollups will incorporate privacy? For dapp developers who want to offer flexible,

user-centric privacy features, NSSA provides a solution through selective privacy.

Consider a dapp running on a transparent network that offers no inherent privacy to its users. Converting this dapp to a privacy-preserving architecture from scratch would

require significant effort, restructuring, and a deep understanding of cryptographic frameworks. However, with NSSA, the dapp does not need to undergo extensive changes.

Instead, the Nescience state-separation model can be deployed as an add-on, offering selective privacy as an option for the dapp’s users.

This allows the dapp to retain its existing functionality while providing users with a choice between the traditional, transparent version and a new version with selective privacy features.

With NSSA, the privacy settings are flexible, meaning users can tailor their level of privacy according to their individual needs while the dapp operates on its current infrastructure.

This contrasts sharply with the typical approach, where dapps are either entirely transparent or fully private, with no flexibility for users to select their own privacy preferences.

A key feature of NSSA is that it operates independently of the privacy characteristics of the host blockchain. Whether the host chain is fully transparent or fully private,

the Nescience state-separation architecture can be deployed on top of it, offering users the ability to choose their own privacy settings.

This decoupling from the host chain’s inherent privacy model is critical as it allows users to benefit from selective privacy even in environments that were not originally designed to offer it.

In fully private chains, NSSA allows users to selectively reveal transaction details when compliance with regulations or other requirements is necessary.

In fully transparent chains, NSSA allows users to maintain privacy for specific transactions, offering flexibility that would not otherwise be possible.

NSSA provides a powerful tool for dapp developers who want to offer selective privacy to their users without the need for a complete overhaul of their existing systems.

By deploying NSSA as an add-on, dapps can give users the ability to choose their own privacy settings whether they are operating on

transparent or private blockchains. This flexibility makes NSSA a valuable option for any dapp looking to provide enhanced privacy options while maintaining efficiency and ease of use.

B. Design

In this section, we will delve into the core design components of the Nescience state-separation architecture, covering its key structural elements and the mechanisms

that drive its functionality. We will explore the following topics:

-

Architecture's components: An in-depth look at the foundational building blocks of NSSA, including the public and private states, UTXO structures, zkVM, and smart contracts.

These components work together to facilitate secure, flexible, and scalable transactions within the architecture.

-

General execution overview: We will outline the overall flow of transaction execution within NSSA, describing how users interact with the system and how the architecture

supports various types of executions—public, private, shielded, and deshielded—while preserving privacy and efficiency.

-

Execution processes and UTXO management: This section will focus on the lifecycle of UTXOs within the architecture, from their generation to consumption.

We will also cover the processes involved in managing UTXOs, including proof generation, state transitions, and ensuring transaction validity.

These topics will provide a comprehensive understanding of how NSSA enables flexible and secure interactions within dapps.

NSSA introduces an advanced prototype execution framework designed to enhance privacy and security in blockchain applications.

This framework integrates several essential components: the public state, private state, zkVM, various execution types, Nescience users, and smart contracts.

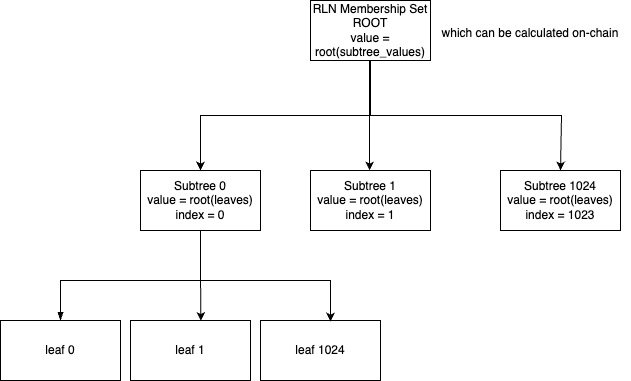

The public state in the NSSA is a fundamental component designed to hold all publicly accessible information within

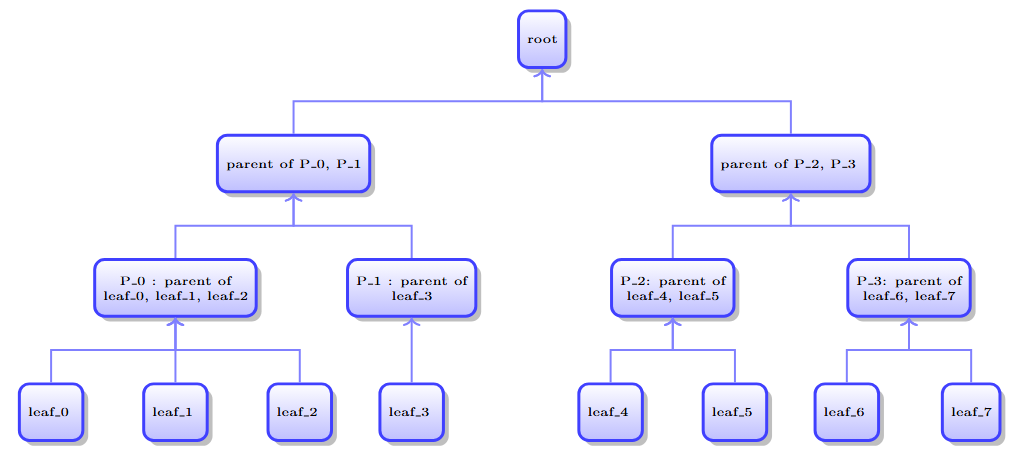

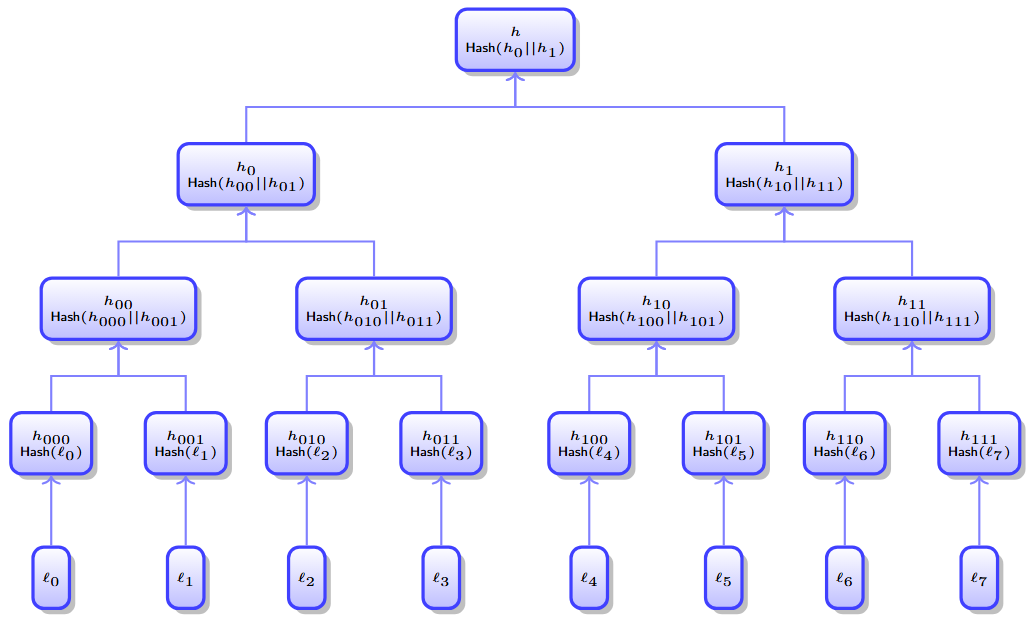

the blockchain network. This state is organized as a single Merkle tree structure, a sophisticated data structure that ensures efficient and secure data verification.

The public state includes critical information such as user balances and the public storage data of smart contracts.

In an account-based model, the public state operates by storing each account or smart contract's public data as individual leaf nodes within the Merkle tree.

When transactions occur, they directly modify the state by updating these leaf nodes. This direct modification ensures that the most current state of the network

is always reflected accurately.

The Merkle tree structure is essential for maintaining data integrity. Each leaf node contains a hash of a data block, and each non-leaf node contains the

hash of its child nodes. This hierarchical arrangement means that any change in the data will result in a change in the corresponding hash, making it easy to detect

any tampering. The root hash, or Merkle root, is stored on the blockchain, providing a cryptographic guarantee of the data's integrity. This root hash serves as a single,

concise representation of the entire state, enabling quick and reliable verification by any network participant.

Transparency is a key feature of the public state. All data stored within this state is openly accessible and verifiable by any participant in the network.

This openness ensures that all transactions and state changes are visible and auditable, fostering trust and accountability. For example, user balances are

publicly viewable, which helps ensure transparency and trust in the system. Similarly, public smart contract storage can be accessed and verified by anyone,

making it suitable for applications that require public scrutiny and auditability, such as public record updates and some financial transactions.

The workflow of managing the public state involves several steps to ensure data integrity and transparency. When a user initiates a transaction involving public data,

the relevant changes are proposed and applied to the public state tree. The transaction details, such as transferring funds between accounts or updating smart contract storage,

update the corresponding leaf nodes in the Merkle tree. Following this, the hashes of the affected nodes are recalculated up to the root, ensuring that the entire tree

accurately reflects the new state of the network. The updated Merkle root is then recorded on the blockchain, allowing all network participants to verify the integrity

of the public state. Any discrepancy in the data will result in a mismatched root hash, signaling potential tampering or errors.

In summary, the public state in NSSA leverages the robustness of the Merkle tree structure to provide a secure, transparent, and verifiable environment for publicly

accessible information. By operating on an account-based model and maintaining rigorous data integrity checks, the public state ensures that all transactions are

transparent and trustworthy, laying a strong foundation for a reliable blockchain network.

The private state in the NSSA is a sophisticated system designed to maintain user privacy while ensuring transaction integrity.

Each user has their own individual Merkle tree, which holds their private information such as balances and storage data. This structure is distinct from the public state,

which uses an account-based model. Instead, the private state employs a UTXO-based model. In this model, each transaction output is a discrete

unit that can be independently spent in future transactions. This design provides users with granular control over their transaction outputs.

A key aspect of maintaining privacy within the private state is the use of ZKPs. ZKPs allow transactions to be validated without revealing any

underlying private data. This means that while the system can verify that a transaction is legitimate, the details of the transaction remain confidential. Only parties

with the appropriate viewing key can access and reconstruct the user’s list of UTXOs, ensuring that sensitive information is protected.

The private state also employs a dual-storage approach to balance privacy and transparency. UTXOs are stored in plaintext within SMTs in the private state,

providing detailed and accessible records for the user. In contrast, the public state only holds hashes of these UTXOs. This method ensures that while the public can verify

the existence and integrity of private transactions through these hashes, they cannot access the specific details.

The workflow for a transaction in the private state begins with the user initiating a transaction involving their private data, such as transferring a private balance or

updating private smart contract storage. The transaction involves spending existing UTXOs, represented as leaves in the Merkle tree, and creating new UTXOs,

which are then appended to the user’s private list. The zkVM generates a ZKP to validate the transaction without revealing

any private data, ensuring the transaction adheres to the system's rules.

Once the proof is generated, it is submitted to the sequencer, which verifies the transaction’s validity. Upon successful verification, the nullifier is added to the nullifier set,

preventing double spending of the same UTXO. The use of ZKPs and nullifiers ensures that the private state maintains both security and privacy.

In summary, the private state in NSSA is meticulously designed to provide users with control over their private information while ensuring the security and integrity of transactions.

By utilizing a UTXO-based model, individual Merkle trees, ZKPs, and a dual-storage system, NSSA achieves a balance between confidentiality and verifiability,

making it a robust solution for managing private blockchain transactions.

The zkVM is a pivotal component in NSSA, designed to uphold the highest standards

of privacy and security in blockchain transactions. Its primary function is to generate and aggregate ZKPs, enabling users to validate the

correctness of their transactions without disclosing any underlying details. This capability is crucial for maintaining the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive

data within the blockchain network.

ZKPs are sophisticated cryptographic protocols that allow one party, the prover, to convince another party, the verifier, that a certain statement is true,

without revealing any information beyond the validity of the statement itself. In the context of the zkVM, this means users can prove their transactions are valid without

exposing transaction specifics, such as amounts or parties involved. This process is essential for transactions within the private state, where maintaining confidentiality is paramount.

The generation of ZKPs involves intricate cryptographic computations. When a user initiates a transaction, the zkVM processes the transaction inputs and produces a proof

that the transaction adheres to the protocol's rules. This proof must be robust enough to convince the verifier of the transaction's validity while preserving the privacy

of the transaction details.

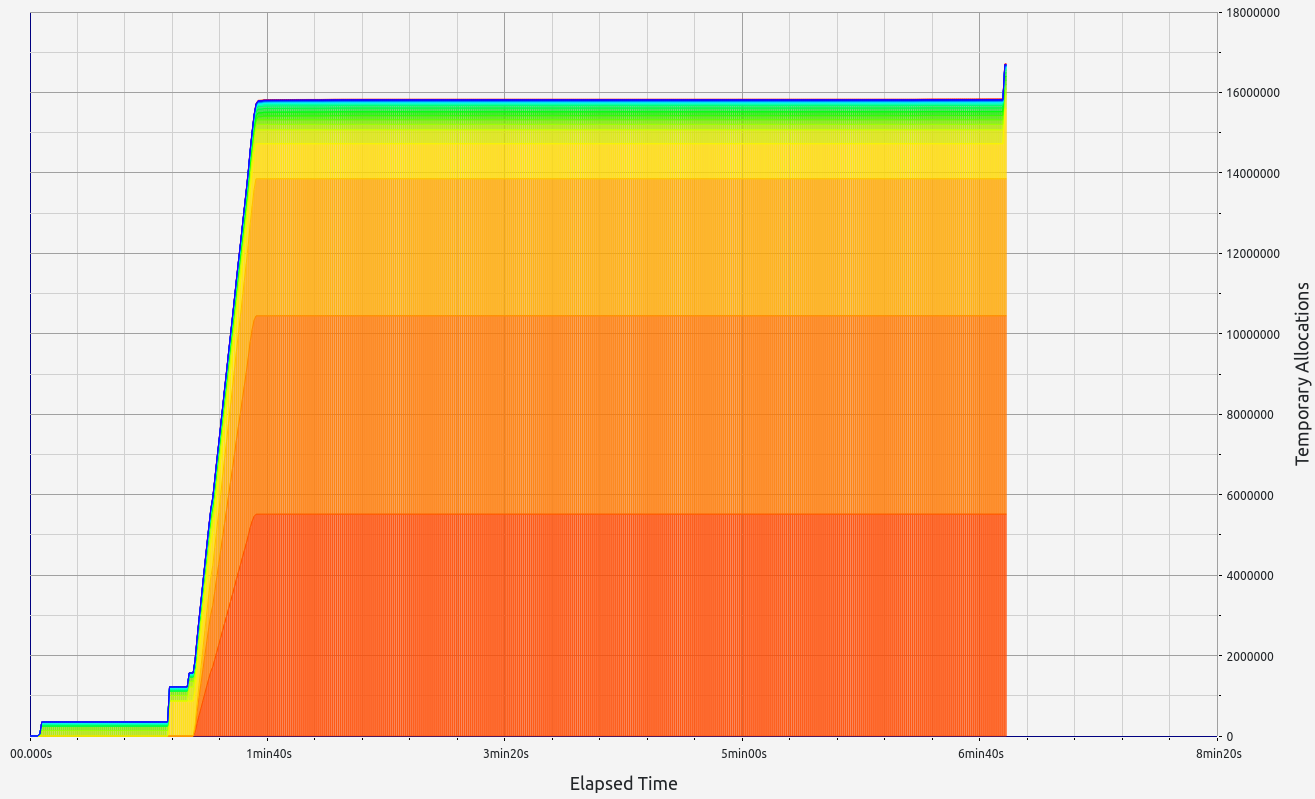

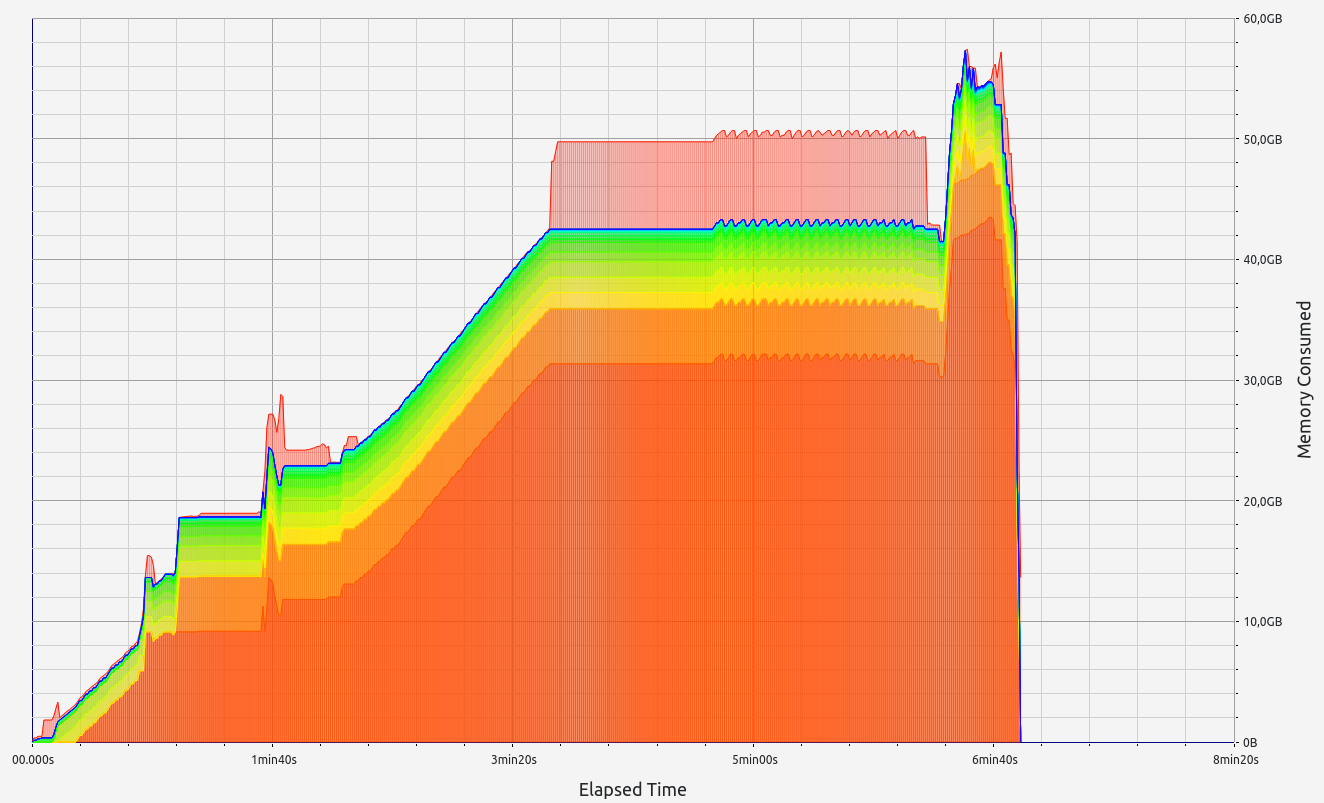

Performance optimization is another critical function of the zkVM. In a typical blockchain scenario, verifying multiple individual proofs can be computationally intensive

and time consuming, potentially leading to network congestion and delays. To address this, the zkVM can aggregate multiple ZKPs into a single, consolidated proof.

This aggregation significantly reduces the verification overhead as the verifier needs to check only one comprehensive proof rather than multiple individual ones.

This efficiency is vital for maintaining high throughput and low latency in the blockchain network, ensuring that the system can handle a large volume of transactions swiftly and securely.

Furthermore, the zkVM's role extends beyond mere proof generation and aggregation. It also ensures that all transactions meet the required privacy and security standards

before they are recorded on the blockchain. By interacting seamlessly with other components such as the public and private states, the zkVM ensures that any transaction,

whether it involves public data, private data, or a mix of both, is thoroughly validated and secured.

In summary, the zkVM is essential for the NSSA, providing the cryptographic backbone necessary to support secure and private transactions. Its ability to generate and

aggregate ZKPs not only preserves the confidentiality of user data but also enhances the overall efficiency and scalability of the blockchain network.

By ensuring that all transactions are validated without revealing sensitive information, the zkVM upholds the integrity and trustworthiness of the Nescience blockchain system.

NSSA incorporates multiple execution types to cater to varying levels of privacy and security requirements.

These execution types—public, private, shielded, and deshielded—are designed to provide users with flexible options for managing their transactions based on their specific privacy needs.

Public executions are straightforward transactions that involve reading from and writing to the public state. In this model, data is openly accessible and verifiable

by all participants in the network. Public executions do not require ZKPs since transparency is the primary goal. This execution type is ideal

for non-sensitive transactions where public visibility is beneficial, such as updating public records, performing open financial transactions, or interacting with public smart contracts.

The workflow for a public execution starts with a user initiating a transaction that modifies public data. The transaction details are then used to update the relevant

leaf nodes in the Merkle tree. As changes are made, the hashes of affected nodes are recalculated up to the root, ensuring that the entire tree reflects the most recent state.

Finally, the updated Merkle root is recorded on the blockchain, making the new state publicly verifiable.

Private executions are designed for confidential transactions, reading from and writing to the private state. These transactions require ZKPs to ensure that while the

transaction details are validated, the actual data remains private. This execution type is suitable for scenarios where privacy is crucial, such as private financial

transactions or sensitive data management within smart contracts.

In a private execution, the user initiates a transaction involving private data. The transaction spends existing UTXOs and creates new ones, all of which are represented as

leaves in the Merkle tree. The zkVM generates a ZKP to validate the transaction without revealing private data. This proof is submitted to the sequencer,

which verifies the proof to ensure the transaction's validity. Upon successful verification, the nullifier is added to the nullifier set, and the private state is updated

with the new Merkle root.

Shielded executions create a layer of privacy for the outputs by allowing interactions between the public and private states. When a transaction occurs in a shielded execution,

details of the transaction are processed within the private state, ensuring that sensitive information remains confidential. Only the necessary details are shared with the public state,

often in a masked or encrypted form. This approach allows for the validation of the transaction without revealing critical data, thus preserving the privacy of the involved parties.

The workflow for shielded executions begins with the user initiating a transaction that reads from the public state and prepares to write to the private state. Public data is accessed,

and the private state is prepared to receive new data. The zkVM generates a ZKP to hide the receiver’s identity. This proof is submitted to the sequencer, which verifies

the proof to ensure the transaction's validity. If valid, the private state is updated with the new data while the public state reflects the change without revealing private details.

This type of execution is particularly useful for scenarios where the receiver’s identity needs to be hidden, such as in anonymous donation systems or confidential data storage.

Deshielded executions operate in the opposite manner of shielded executions, where data is read from the private state and written to the public state. This execution type is useful

in situations where the sender's identity needs to be kept confidential while making the transaction results publicly visible.

In a deshielded execution, the user initiates a transaction that reads from the private state and prepares to write to the public state. Private data is accessed,

and the transaction details are prepared. The zkVM generates a ZKP to hide the sender’s identity. This proof is then submitted to the sequencer,

which verifies the proof to ensure the transaction's validity. Once verified, the public state is updated with the new data, reflecting the change while keeping the sender’s

details confidential. This can be useful when transparency is needed, such as when auditing or proving certain aspects of a transaction to a wider audience.

By selectively deshielding certain transactions, users can control what information is shared publicly, thus maintaining a balance between privacy and transparency

as required by their specific use case.

| Type | Read from | Write to | ZKP required | Use case | Description |

|---|

| Public | Public state | Public state | No | Non-sensitive transactions requiring transparency. | Ideal for transactions that do not require privacy, ensuring full transparency. |

| Private | Private state | Private state | Yes | Confidential transactions needing privacy. | Suitable for transactions that require confidentiality. Ensures that transaction details remain private through the use of ZKPs. |

| Shielded | Public state | Private state | Yes | Transactions where the receiver’s identity needs to be hidden. | Hides the identity of the receiver while keeping the transaction details private. Suitable for anonymous donations or confidential data storage. |

| Deshielded | Private state | Public state | Yes | Transactions where the sender’s identity needs to be hidden. | Ensures the sender’s identity remains confidential while making the transaction results public. Suitable for confidential disbursements or anonymized data publication. |

By supporting a range of execution types, NSSA provides a flexible and robust framework for managing privacy and security in blockchain transactions.

Whether the need is for complete transparency, total privacy, or a balanced approach, NSSA's execution types allow users to select the level of confidentiality

that best fits their requirements. This flexibility enhances the overall utility of the blockchain, making it suitable for a wide array of applications and use cases.

Nescience users are integral to the architecture, managing balances and assets within the blockchain network and invoking smart contracts with various privacy options.

They can choose the appropriate execution type—public, private, shielded, or deshielded—based on their specific privacy and security needs.

Users handle both public and private balances. Public balances are visible to all network participants and suitable for non-sensitive transactions,

while private balances are confidential and used for transactions requiring privacy. Digital wallets provide a user-friendly interface for managing

these balances, assets, and transactions, allowing users to select the desired execution type seamlessly.

Security is ensured through the use of cryptographic keys, which authenticate and verify transactions. ZKPs maintain privacy

by validating transaction correctness without revealing underlying data, ensuring sensitive information remains confidential even during verification.

The workflow for users involves initiating a transaction, preparing inputs, interacting with smart contracts, generating proofs if needed,

and submitting the transaction to the sequencer for verification and state update. This flexible approach supports various use cases,

from financial transactions and decentralized applications to data privacy management, allowing users to maintain control over their privacy settings.

By offering this high degree of flexibility and security, Nescience enables users to tailor their privacy settings to their specific needs,

ensuring sensitive transactions remain confidential while non-sensitive ones are transparent. This integration of cryptographic keys and ZKPs

provides a robust framework for a wide range of blockchain applications, enhancing both utility and trust within the network.

Smart contracts are a core feature of NSSA, providing a way to automate and execute predefined actions based on coded rules.

Once deployed on the blockchain, these contracts become immutable, meaning their behavior cannot be altered. This ensures that they perform exactly as

intended without the risk of tampering. Because the state and data of the contract are stored permanently on the blockchain, all interactions are fully

transparent and auditable, creating a reliable and trustworthy environment.

One of the key strengths of smart contracts is their ability to automate processes. They are designed to automatically execute when specific conditions are met,

reducing the need for manual oversight or intermediaries. For example, a smart contract might transfer funds when a certain deadline is reached or update a record

once a task is completed. This self-executing nature makes them efficient and minimizes human error.

Smart contracts operate deterministically, meaning they will always produce the same result given the same inputs. This predictability is crucial for ensuring reliability,

especially in complex systems. Additionally, they run in isolated environments on the blockchain, which enhances security by preventing unintended interactions with other processes.

Security is another critical feature of smart contracts. They leverage the underlying cryptographic protections of the blockchain, ensuring that every interaction

is secure and authenticated. Before deployment, the contract code can be audited and verified to ensure it functions correctly. Once on the blockchain,

the immutable nature of the code prevents unauthorized modifications, further ensuring the integrity of the system.

Running smart contracts requires computational resources, which are compensated through gas fees. These fees vary depending on the complexity of the operations within the contract.

More resource-intensive contracts incur higher fees, which helps manage the computational load on the blockchain network.

The workflow of a smart contract begins with its development, where developers code the contract using languages like Rust. Once the code is compiled and deployed to the blockchain,

it becomes a permanent part of the network. Users can then interact with the contract by sending transactions that invoke specific functions. The contract checks whether the

required conditions are met, and if so, it automatically executes the specified actions, such as transferring tokens or updating data on the blockchain.

The benefits of smart contracts are numerous. They eliminate the need for intermediaries by providing a system where trust is built into the code itself.

This not only reduces costs but also increases efficiency by automating repetitive processes. The inherent security of smart contracts, combined with their

transparency—where every action is recorded and visible on the blockchain—makes them a powerful tool for ensuring accountability and trust in decentralized systems.

They can be ideal for managing decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), where governance decisions are automated through coded rules.

By integrating smart contracts, NSSA offers a highly versatile, secure, and transparent framework that can support a wide range of applications

across various industries, from finance to governance, supply chains, and more.

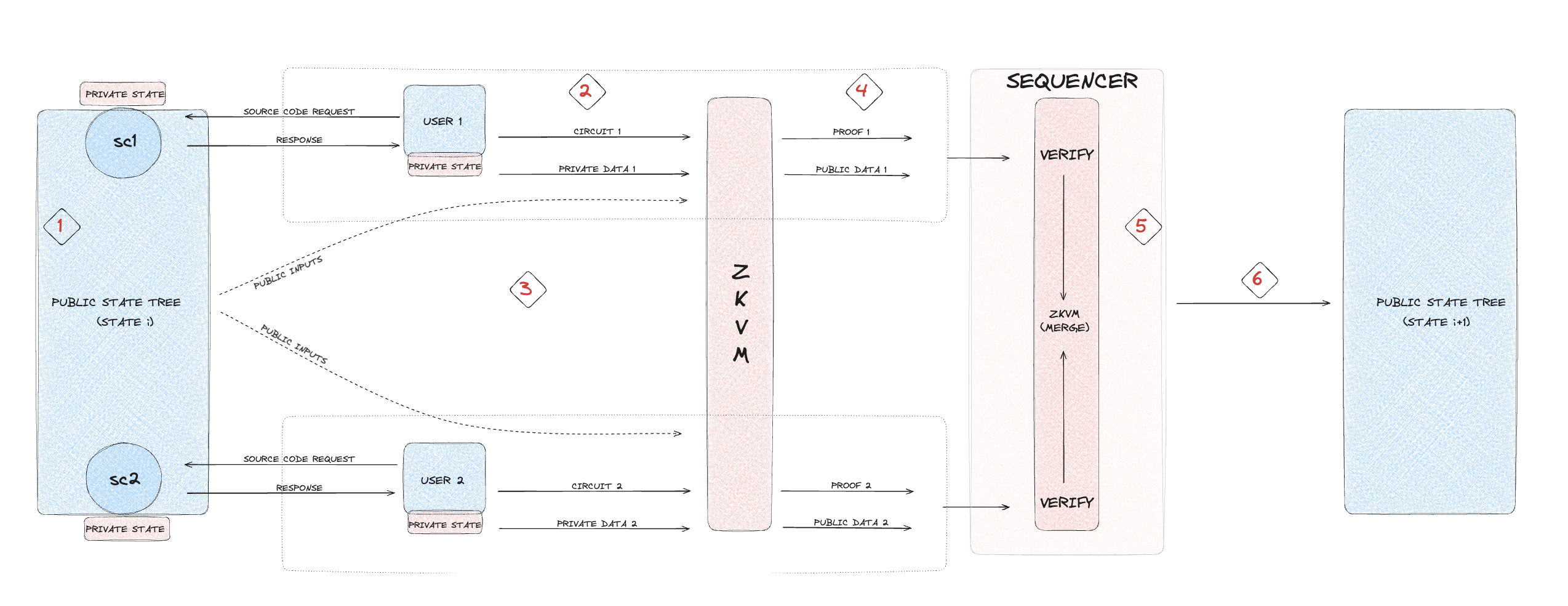

This section explains the execution process within NSSA, providing an overview of how it works from start to finish.

It outlines the steps involved in each execution type, guiding the reader through the entire process from user interaction to completion.

The process begins when a user initiates a transaction by invoking a smart contract. This invocation involves selecting at least one of

the four execution types: public, private, shielded, or deshielded. The choice of execution type determines how data will be read from and written to the blockchain,

affecting the transaction's privacy and security levels. Each execution type caters to different privacy needs, allowing the user to tailor the transaction according

to their specific requirements, whether it be full transparency or complete confidentiality.

Step 1: Smart contract selection and input creation

- Smart contract selection: The user selects a smart contract they wish to invoke.

- Input creation: The user creates a set of inputs required for the invocation by reading the necessary data from both the public and private states. This includes:

- Public data such as current account balances, public keys, and smart contract states.

- Private data such as private account balances and UTXOs.

Step 2: Choosing execution type

- Execution type selection: The user selects the type of execution based on their privacy needs. The options include:

- Public execution: Suitable for transactions where transparency is desired.

- Private execution: Used when transaction details need to be confidential.

- Shielded execution: Hides the receiver's identity.

- Deshielded execution: Hides the sender's identity.

- ZkVM requirement: If the execution involves private, shielded, or deshielded types, the user must call the zkVM to handle these confidential transactions.

For purely public executions, the zkVM is not needed, and the user can directly transmit the transaction code to the sequencer.

Step 3: Calling zkVM for proof generation

- ZkVM compilation: The user calls the zkVM to compile the smart contract with both public and private inputs.

- Kernel circuit proofs: The zkVM generates individual proofs for each execution type through kernel circuits.

- Proof aggregation: The zkVM aggregates these individual proofs into a single comprehensive proof, combining both private and public inputs.

Step 4: Transmitting public inputs and retaining private inputs

- Retaining private inputs: The user keeps the private inputs secure and does not transmit them.

- Revealing public inputs: The user transmits the following public inputs to the sequencer:

- Public inputs of the recursive proof

- Hashes of UTXOs

- Updates to the public state

- Transaction signature

- Nullifiers (to prevent double spending)

After completing these steps, the user's part of the execution is done, and the sequencer takes over the process.

Step 5: Proof verification

- Proof and data reception: The sequencer receives the proof and public inputs from the user.

- Verification process:

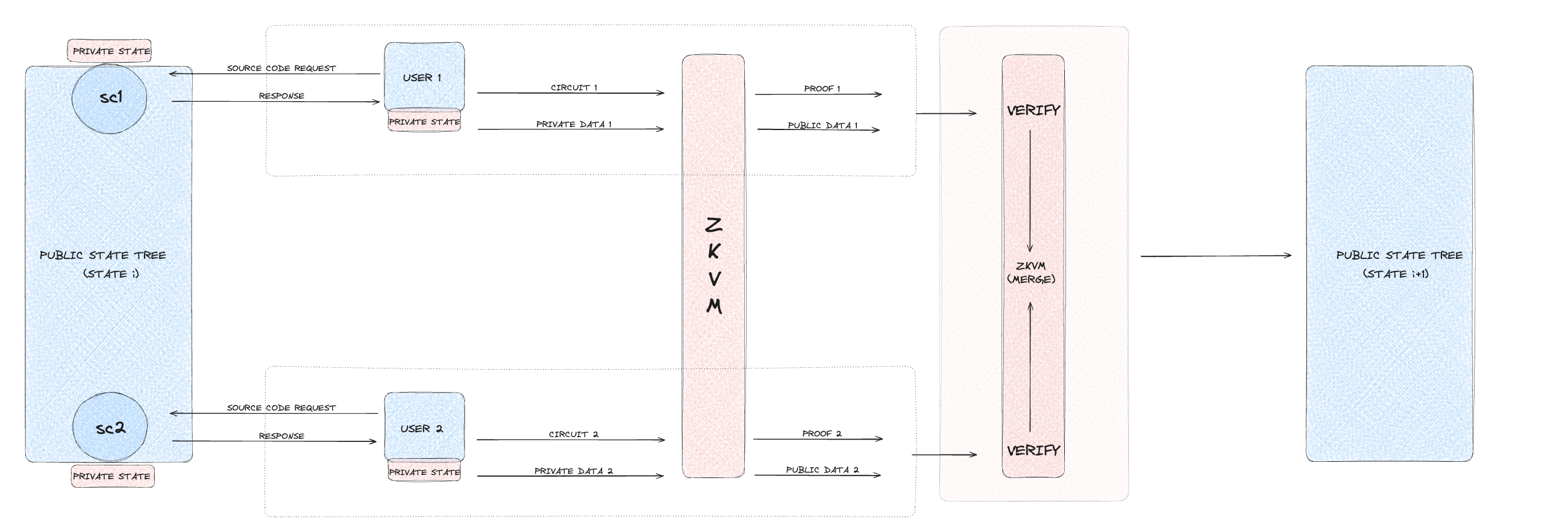

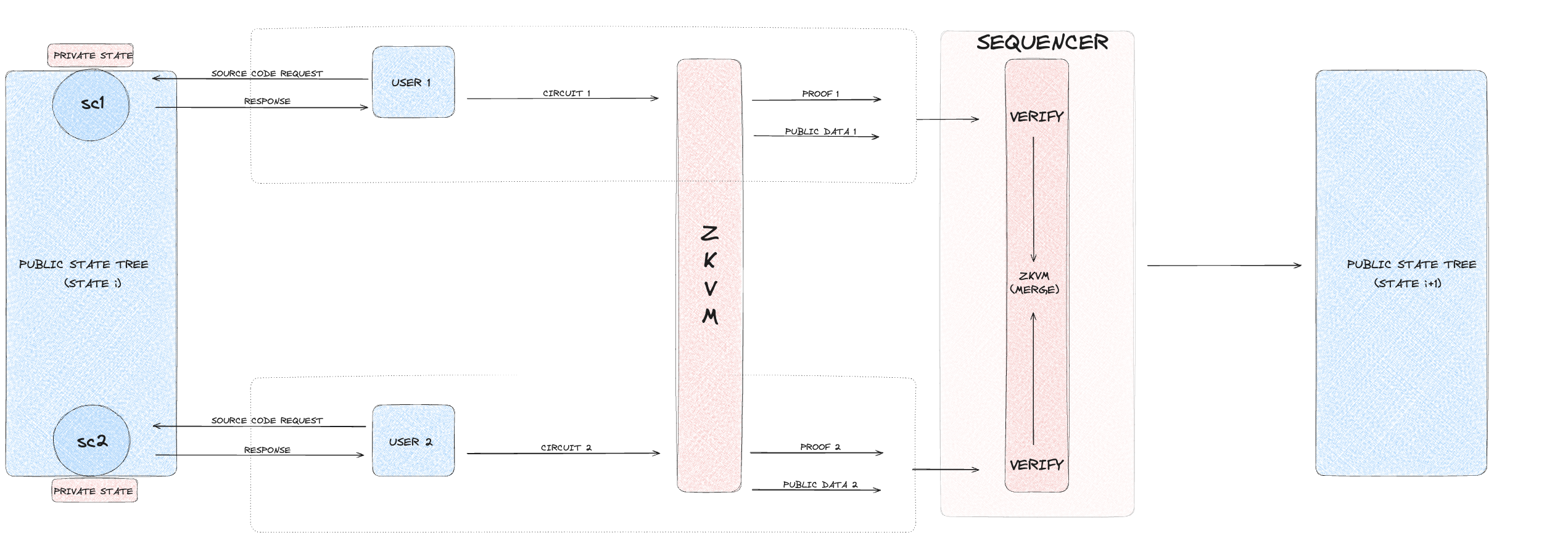

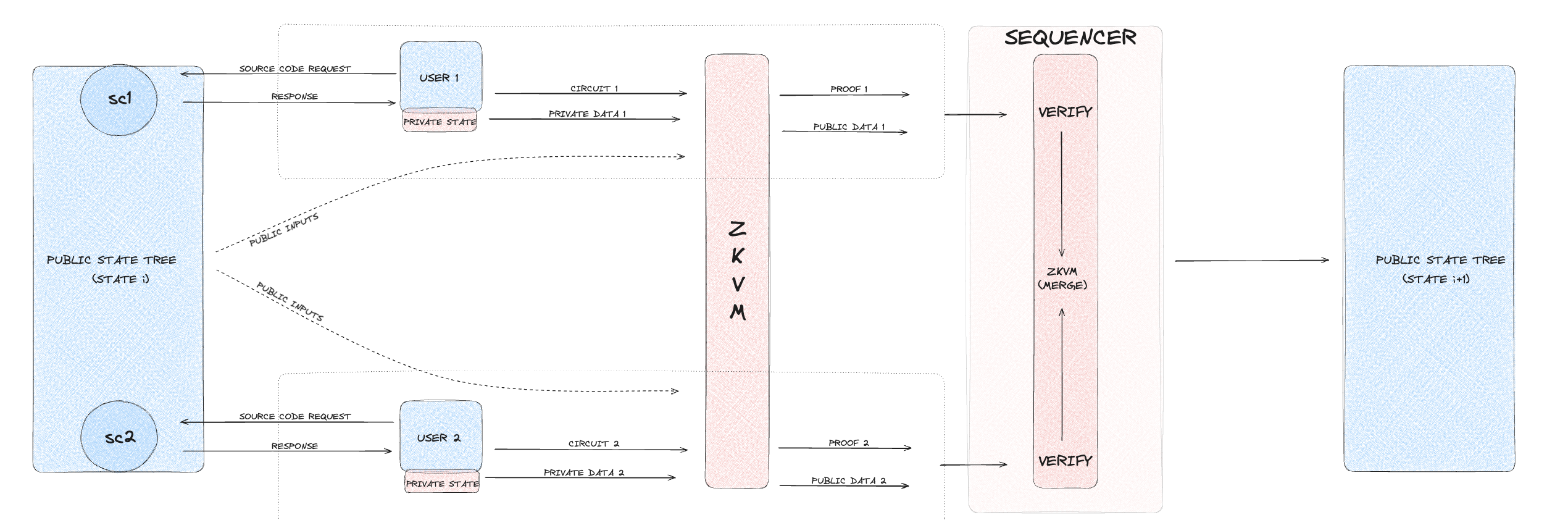

- For private, shielded, and deshielded executions, the sequencer verifies the proof using the provided public data.

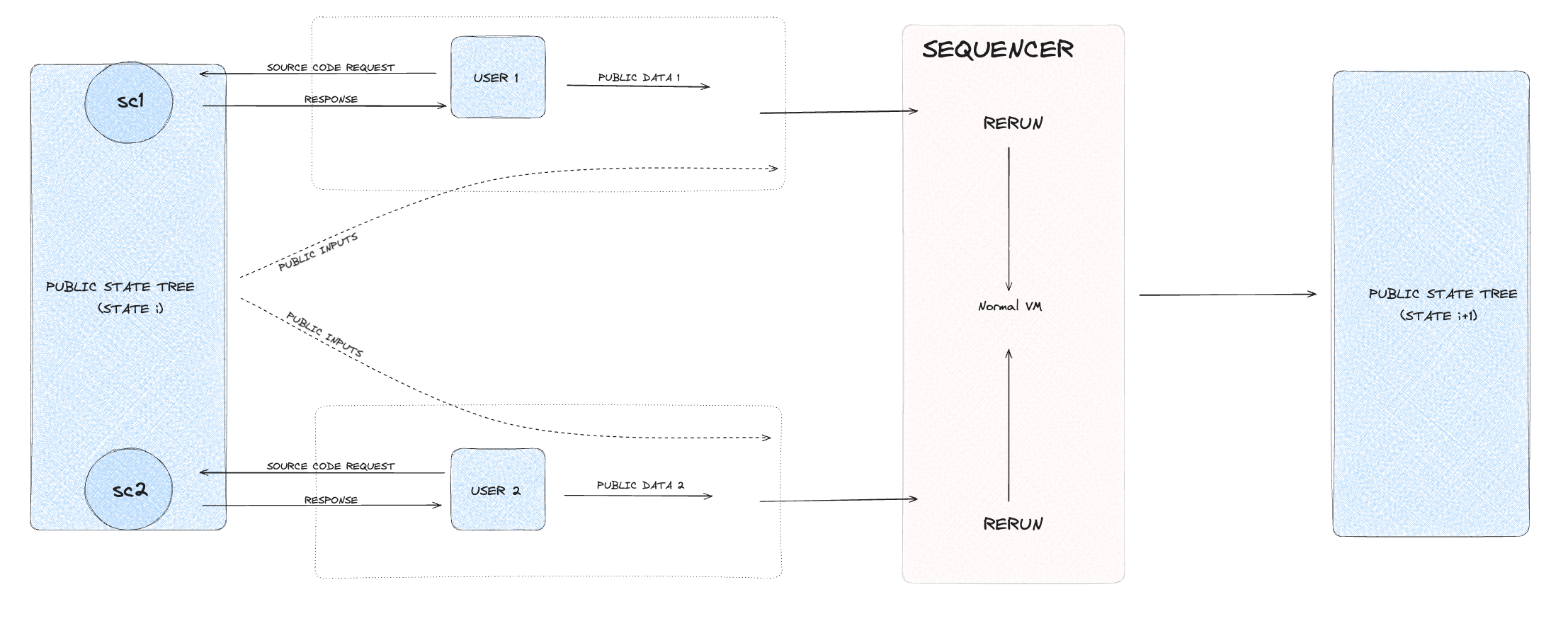

- For public executions, the sequencer reruns the smart contract code with the provided inputs to check the results.

- Validation: If both the zkVM proofs and public execution results are verified successfully, the sequencer collects the proof and public data to proceed.

If verification fails, the process is aborted, and the transaction is rejected.

Step 6: Aggregating proofs and finalizing the block

- Proof aggregation: The sequencer calls the zkVM again to aggregate all received proofs into one comprehensive proof to finalize the block.

- Finalizing the block:

- Public state update: The sequencer updates the public state with the new transaction data.

- Nullifier tree update: Updates the nullifier tree to reflect the new state and prevent double spending.

- Synchronization mechanism: Runs synchronization mechanisms to ensure fairness and consistency across the network.

- UTXO validation: Validates the exchanged UTXOs to complete the transaction process.

This comprehensive process ensures that transactions are executed securely, with the appropriate level of privacy and state updates synchronized across the network.

Below, we outline the execution process of the four different execution types within NSSA:

In Nescience state-separation architecture, UTXOs are key components for managing private data and assets. They serve as private entities that hold both storage and assets,

facilitating secure and confidential transactions. UTXOs are utilized in three of the four execution types within NSSA: private, shielded,

and deshielded executions. This section explores the lifecycle of UTXOs, detailing their generation, transfer, encryption, and eventual consumption within the private execution framework.

A Nescience UTXO is a critical and versatile component of the private state in the Nescience state-separation architecture.

It carries essential information that ensures its proper functionality within private execution, such as the owner, value, private storage slot, non-fungibles,

and other cryptographic components. Below is a detailed breakdown of each component and its role in maintaining the integrity, security, and privacy of the system:

-

Owner:

The owner component represents the public key of the entity that controls the UTXO. Only the owner can spend this UTXO, ensuring its security and privacy through public key cryptography.

This means that the UTXO remains secure as only the rightful owner, using their private key, can generate valid signatures to authorize the transaction. For example,

if Alice owns a UTXO linked to her public key, she must sign any transaction to spend it using her private key. This cryptographic protection ensures that only Alice can authorize

spending the UTXO and transfer it to someone else, such as Bob.

-

Value:

The value in a UTXO represents the balance or asset contained within it. This could be cryptocurrency, tokens, or other digital assets. The value ensures accurate accounting,

preventing double spending and maintaining the overall integrity of the system. For instance, if Alice's UTXO has a value of 10 tokens, this represents her ownership of that amount

within the network, and when spent, this value will be deducted from her UTXO and transferred accordingly.

-

Private storage slot:

The private storage slot is an arbitrary and flexible storage space within the UTXO for Nescience applications. It allows users and smart contracts to store additional private data

that is only accessible by the owner. This could be used to hold metadata, smart contract states, or user-specific information. For example, if a smart contract is holding private user data,

this information is securely stored in the private storage slot and can only be accessed or modified by the owner, ensuring privacy and security.

-

Non-fungibles:

Non-fungibles within the UTXO represent unique assets, such as NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens). Each non-fungible asset is assigned a unique serial number or identifier within the UTXO,

ensuring its distinctiveness and traceability. For example, if Alice owns a digital artwork represented as an NFT, the non-fungible component of the UTXO will store the unique identifier

for this NFT, preventing duplication or forgery of the digital asset.

-

Random commitment key:

The random commitment key (RCK) is a randomly generated number used to create a cryptographic commitment to the contents of the UTXO. This commitment ensures the integrity of the data

without revealing any private information. By generating a random key for the commitment, the system ensures that even if someone observes the commitment, they cannot infer any details

about the underlying UTXO. For example, RCK helps maintain confidentiality in the system while still allowing the verification of transactions.

-

Nullifier key:

The Nullifier key is another randomly generated number, used to ensure that a UTXO is only spent once. When a UTXO is spent, its nullifier key is recorded in a nullifier set to prevent

double spending. This key guarantees that once a UTXO is spent, it cannot be reused in another transaction, effectively nullifying it from future use. This mechanism is crucial for

maintaining the security and integrity of the system, as it ensures that no UTXO can be spent more than once.

UTXOs in NSSA are created when a transaction outputs a specific value, asset, or data intended for future use. Once generated, these UTXOs become private entities

owned by specific users, containing sensitive information such as balances, private data, or unique assets like NFTs.

To maintain the required level of confidentiality, UTXOs are encrypted and transferred anonymously across the network. This encryption process ensures that the data within each UTXO

remains hidden from network participants, including the sequencer, while still allowing for verification and validation through ZKPs. These proofs enable the network

to ensure that UTXOs are valid, prevent double spending, and maintain security, all without revealing any sensitive information.

When a user wishes to spend or transfer a UTXO, the lifecycle progresses towards its consumption. The user must prove ownership and validity of the UTXO through a ZKP,

which is then verified by the sequencer. This process occurs in private, shielded, and deshielded executions, where confidentiality is a priority. Once the proof is validated,

the UTXO is consumed, meaning it is marked as spent and cannot be reused, ensuring the integrity of the transaction and preventing double spending.

UTXOs are central to the private, shielded, and deshielded execution types in Nescience. In private executions, UTXOs are transferred securely between parties without revealing any

details to the public state. In shielded executions, UTXOs are used to receive assets from the public state while keeping the recipient's identity confidential. Finally,

in deshielded executions, UTXOs are used to send assets from the private state to the public state, while preserving the sender's anonymity.

Since UTXOs are not exchanged in public executions, this lifecycle analysis is focused solely on private, shielded, and deshielded executions, where privacy and confidentiality are essential.

In these contexts, the careful management and transfer of UTXOs ensure that the users' private data and assets remain secure, while still allowing for seamless and confidential transactions

within the network.

At this point, it's crucial to introduce two key components that will play a significant role in the next section: the ephemeral key and the nillifier.

-

Ephemeral key: The ephemeral key is embedded in the transaction message and plays a crucial role in maintaining privacy. It is used by the sender, alongside the receiver's public key,

in a key agreement protocol to derive a shared secret. This shared secret is then employed to encrypt the transaction details, ensuring that only those with the receiver's viewing key can

decrypt the transaction. By using the ephemeral key, the receiver can regenerate the shared secret, granting access to the transaction's contents. The sender generates the ephemeral key

using their spending key and the UTXO's nullifier, reinforcing the security of the transaction. (more details in key management and addresses section)

-

Nullifier: A nullifier is a unique value tied to a specific UTXO, ensuring that it has not been spent before. Its uniqueness is essential, as a nullifier must never correspond to more

than one UTXO—otherwise, even if both UTXOs are valid, only one could be spent. This would undermine the integrity of the system. To spend a UTXO, a proof must be provided showing that

the nullifier does not already exist in the Nullifier Tree. Once the transaction is confirmed and included in the blockchain, the nullifier is added to the Nullifier Tree, preventing any

future reuse of the same UTXO. A UTXO's nullifier is generated by combining the receiver's nullifier key with the transaction note's commitment, further ensuring its distinctiveness

and security. (More details in nullifier tree section.)

In private executions within NSSA, transactions are handled ensuring maximum privacy by concealing all transaction details from the public state.

This approach is particularly useful for confidential payments, where the identities of the sender and receiver, as well as the transaction amounts, must remain hidden.

The process is powered by ZKPs, ensuring that only the involved parties have access to the transaction details while maintaining the integrity of the network.

-

Stages of private execution: Private executions operate in two key stages: UTXO consumption and UTXO creation. In the first stage, UTXOs from the private state are used

as inputs for the transaction. In the second stage, new UTXOs are generated as outputs and stored back in the private state. Throughout this process, the details of the

transaction are kept confidential and only shared between the sender and receiver.

-

Private transaction workflow (transaction initialization): The user initiates a private transaction by selecting the input UTXOs that will be spent and determining the

output UTXOs to be created. This involves specifying the amounts to be transferred and the recipient’s private address (a divestified address that hides the recipient's public

address from the network). The nullifier key and random number for commitments (RCK) are also generated at this stage to define how these UTXOs can be spent or nullified in the

future by the receiver.

-

Proof generation and verification: Next, the zkVM generates a ZKP to validate the transaction. This proof includes both a membership proof for the input UTXOs,

confirming their presence in the hashed UTXO tree, and a non-membership proof to ensure that the input UTXOs have not already been spent (i.e., they are not in the nullifier tree).

The proof also confirms that the total input value matches the total output value, ensuring no discrepancies. The user then submits the proof, along with the necessary metadata, to the sequencer.

-

Shared secret and encryption: To maintain confidentiality, the sender uses the receiver’s divestified address to generate an ephemeral public key.

This allows the creation of a shared secret between the sender and receiver. Using a key derivation function, a symmetric encryption key is generated from the shared secret.

The input and output UTXOs are then encrypted using this symmetric key, ensuring that only the intended recipient can decrypt the data.

-

Broadcasting the transaction: The user broadcasts the encrypted UTXOs to the network, along with a commitment to the output UTXOs using Pedersen hashes.

These committed UTXOs are sent to the sequencer, which updates the hashed UTXO tree without knowing the transaction details.

-

Decryption by the receiver: After the broadcast, the receiver attempts to decrypt the broadcast UTXOs using their symmetric key, derived from the ephemeral public key.

If the receiver successfully decrypts a UTXO, it confirms ownership of that UTXO. The receiver then computes the nullifier for the UTXO and verifies its presence in the hashed

UTXO tree and its absence from the nullifier tree, ensuring it has not been spent. Finally, the new UTXO is added to the receiver’s locally stored UTXO tree for future transactions.

Throughout the private execution process, the identities of both the sender and receiver, as well as all transaction details, remain hidden from the public.

The use of ZKPs ensures that the integrity of the transaction is verified without revealing any sensitive information. At the end of the process,

the network guarantees that no participant, aside from the sender and receiver, can deduce any details about the transaction or the involved parties.

In shielded executions, the interaction between public and private states provides a hybrid privacy model that balances transparency and confidentiality.

This model is suitable for scenarios where the initial step, such as a public transaction, requires visibility, while subsequent actions, such as private asset management,

need to remain confidential. One common use case is asset conversion—where a public token is converted into a private token. The conversion is visible on the public ledger,

but subsequent transactions remain private.

Shielded executions operate in two distinct stages: first, there is a modification of the public state, and then new UTXOs are created and stored in the private state.

Importantly, shielded executions do not consume UTXOs but instead mint them, as new UTXOs are created to reflect the changes in the private state. This structure demands

ZKPs to ensure that the newly minted UTXOs are consistent with the modifications in the public state. Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how the shielded

execution process unfolds:

-

Transaction initiation: The user initiates a transaction that modifies the public state, such as converting a public token to a private token.

The transaction alters the public state (e.g., balances or smart contract storage) while simultaneously preparing to mint new UTXOs in the private state.

-

Generating UTXOs: After modifying the public state, the system mints new UTXOs in the private state. These UTXOs must be securely created, ensuring their integrity

and consistency with the initial public state modification. A ZKP is generated by the user to prove that these new UTXOs align with the changes made in the public state.

-

Key setup for privacy: The sender retrieves the receiver's address and uses it to create a shared secret through an ephemeral public key. This shared secret is then used

to derive a symmetric key, which encrypts the output UTXOs. This encryption ensures that only the intended receiver can decrypt and access the UTXOs.

-

Broadcasting and verifying UTXOs: After encrypting the UTXOs, the sender broadcasts them to the network. The new hashed UTXOs are sent to the sequencer,

which verifies the validity of the UTXOs and attaches them to the hashed UTXO tree within the private state. The public inputs for the ZKP circuits consist of the

Pedersen-hashed UTXOs and the modifications in the public state.

-

Receiver's role: Once the UTXOs are broadcast, the receiver attempts to decrypt each UTXO using the symmetric key derived from the shared secret. If the decryption is successful,

the UTXO belongs to the receiver. The receiver then verifies the UTXO’s validity by checking its inclusion in the hashed UTXO tree and ensuring that its nullifier has not yet been used.

-

Nullifier check and integration: To prevent double spending, the receiver computes the nullifier for the received UTXO and verifies that it is not already present in the nullifier tree.

Once verified, the receiver adds the UTXO to their locally stored UTXO tree for future use in private transactions.

While shielded executions offer privacy, certain information is still exposed to the public state, such as the sender's identity. To further enhance privacy,

the sender can create empty UTXOs—UTXOs that don’t belong to anyone but are included in the transaction to obfuscate the true details of the transaction.

Though this approach increases the size of the data, it adds a layer of privacy by complicating the identification of meaningful transactions.

- Stage 1 (public modification): The user modifies public state data, such as converting tokens from public to private. This stage is visible to the public.

- Stage 2 (UTXO minting and privacy): New UTXOs are minted in the private state, encrypted, and broadcast to the network. The transaction remains private from this point forward,

secured by ZKPs and cryptographic keys.

- Receiver’s role: The receiver decrypts the UTXOs and verifies their validity, ensuring the UTXOs are not double spent and are ready for future transactions.

In summary, shielded executions enable a hybrid privacy model in Nescience, balancing public transparency and private confidentiality. They are well-suited for

transactions requiring initial public visibility, such as asset conversions, while ensuring that subsequent actions remain secure and private within the network.

In NSSA, deshielded executions offer a unique way to move data and assets from the private state to the public state, revealing previously private

information in a controlled and verifiable manner. This type of execution allows for selective disclosure, ensuring transparency when needed while still maintaining

the security and privacy of critical details through cryptographic techniques like ZKPs. Deshielded executions are particularly valuable for use cases

such as regulatory compliance reporting, where specific transaction details must be revealed to meet legal requirements, while other sensitive transactions remain private.

-

Stage 1 (UTXO consumption): The process begins in the private state, where UTXOs are consumed as inputs for the transaction. This involves gathering all necessary

UTXOs that contain the assets or balances to be made public, as well as any associated private data stored in memory slots.

-

Stage 2 (public state modification): After the UTXOs are consumed, the transaction details are made public by modifying the public state. This update includes changes

to the public balances, storage data, and any necessary public records. While the public state is updated, the sender’s identity and other sensitive information remain hidden,

thanks to the privacy-preserving properties of ZKPs.

This model ensures that private data can be selectively revealed when needed, offering both flexibility and transparency. It is particularly useful for scenarios requiring

auditing or compliance reporting, where specific details must be made publicly verifiable without exposing the entire history or contents of private transactions.

The deshielded execution process starts when a user initiates a transaction using private UTXOs. The Nescience zkVM is called to generate a ZKP,

which validates the transaction without revealing sensitive details such as the sender's identity or the specifics of the Nescience application being executed.

During the transaction, the UTXOs from the private state are consumed, meaning they are used up as inputs and will no longer be available for future transactions.

Instead of generating new UTXOs, the transaction modifies the public state, updating the necessary balances or memory slots related to the transaction.

Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how the deshielded execution process unfolds:

-

Get receiver's public address: The sender first identifies the public address of the receiver, to which the information or assets will be made public.

-

Determine input UTXOs and public state modifications: The sender gathers all the input UTXOs needed for the transaction and determines the public state modifications

necessary for the Nescience applications and token transfers involved.

-

Calculate nullifiers: Nullifiers are generated for each input UTXO, ensuring that these UTXOs cannot be reused or double spent. The nullifiers are derived from the

corresponding UTXO commitments.

-

Call zkVM with deshielded circuits: The sender invokes the zkVM with deshielded kernel circuits, which generates the proof. The proof ensures that all input UTXOs

are valid by verifying their membership in the UTXO tree and their non-membership in the nullifier tree, ensuring they haven’t been spent.

-

Generate and submit proof: The zkVM generates a ZKP that verifies the correctness of the transaction without revealing private details.

The proof includes the nullifiers and the planned modifications to the public state.

-

Send proof to sequencer: The sender then sends the proof and any relevant public information to the sequencer. The sequencer is responsible for verifying the proof,

updating the public state accordingly, and adding the nullifiers to the nullifier tree.

Once the proof and public information have been broadcast to the network, the receiver does not need to take any further action.

The sequencer manages the public state updates and ensures that the transaction is properly executed. By the end of the deshielded execution,

specific transaction details become publicly visible, such as the identity of the receiver and the outcome of the transaction.

This allows participants in the public state to extract information about the transaction, including the receiver's identity and some details about the execution.

While the receiver's identity is revealed, the sender's identity and sensitive transaction details remain hidden, thanks to the use of ZKPs.

This makes deshielded executions ideal for cases where transparency is needed, but complete privacy is still a priority for certain elements of the transaction.

In NSSA, consuming UTXOs is a critical step in maintaining the security and integrity of the blockchain by preventing double spending.

When a UTXO is consumed, it is used as an input in a transaction, effectively marking it as spent. This ensures that the UTXO cannot be reused, preserving the integrity of the blockchain.

- The process of consuming UTXOs: The process of consuming a UTXO begins when a user selects a UTXO from their private state. The user verifies the UTXO’s existence and

ownership using their viewing key, ensuring that they are the legitimate owner of the UTXO. Once verified, the user generates two key cryptographic proofs:

- Membership proof: This proof confirms that the UTXO exists within the hashed UTXO tree, ensuring its validity within the system.

- Non-membership proof: This proof ensures that the UTXO has not been previously consumed by checking its absence in the nullifier tree, which tracks spent UTXOs.

To mark the UTXO as spent, a nullifier is generated. This nullifier is a unique cryptographic hash derived from the UTXO, which is then added to the nullifier tree in the public state.

Adding the nullifier to the tree prevents the UTXO from being reused in future transactions, thus preventing double spending.

After generating the membership and non-membership proofs, the user compiles the transaction using the zkVM. The zkVM is responsible for generating the necessary ZKPs,

which validate the transaction without revealing sensitive details. The compiled transaction, along with the proofs, is then submitted to the sequencer for verification.

- The role of the sequencer: Once the transaction is submitted, the sequencer verifies the ZKPs to confirm that the transaction is valid. If the proofs are verified

successfully, the sequencer updates both the private and public states to reflect the transaction. This includes updating the nullifier tree with the newly generated nullifier,

ensuring that the UTXO is marked as spent and cannot be reused.

Consider an example where Alice wants to send 5 Nescience tokens to Bob using a private execution. Alice selects a UTXO from her private state that contains 5 Nescience tokens.

She generates the necessary membership and non-membership proofs, ensuring that her UTXO exists in the system and has not been previously spent. Alice then creates a nullifier by

hashing the UTXO and compiles the transaction with the zkVM.

Once Alice submits the transaction, the sequencer verifies the proofs and updates the blockchain by adding the nullifier to the nullifier tree and recording the transaction details.

This ensures that Alice’s UTXO is marked as spent and cannot be used again, while Bob receives the 5 tokens.

Nullifiers are a key mechanism in preventing double spending. By marking consumed UTXOs as spent and tracking them in the nullifier tree, NSSA ensures that

once a UTXO is used in a transaction, it cannot be reused in any future transactions. This process is fundamental to maintaining the integrity and security of the blockchain,

as it guarantees that assets are only spent once and prevents potential attacks on the system.

In conclusion, the process of consuming UTXOs in NSSA combines cryptographic proofs, nullifiers, and ZKPs to ensure that transactions

are secure, confidential, and free from the risks of double spending.

C. Cryptographic primitives in NSSA

In the NSSA, cryptographic primitives are the foundational elements that ensure the security, privacy, and efficiency of the state separation model.

These cryptographic tools enable private transactions, secure data management, and robust verification processes across both public and private states.

The architecture leverages a wide range of cryptographic mechanisms, including advanced hash functions, key management systems, tree structures, and ZKPs,

to safeguard user data and maintain the integrity of transactions.

Cryptographic hash functions play a pivotal role in concealing UTXO details, generating nullifiers, and constructing sparse Merkle trees, which organize and verify

data efficiently within the network. Key management and address generation further enhance the security of user assets and identity, ensuring that only authorized

users can access and control their holdings.

The architecture also relies on specialized tree structures for organizing data, verifying the existence of UTXOs, and tracking nullifiers, which prevent double spending.

Additionally, Nescience features a privacy-preserving zero-knowledge virtual machine (zk-zkVM), which allows users to prove the correctness of an execution without

disclosing sensitive information. This enables private transactions and maintains confidentiality across the network.

As Nescience evolves, optional cryptographic mechanisms such as multi-party computation (MPC) may be integrated to enhance synchronization across privacy levels.

This MPC-based synchronization mechanism is still under development and under review for potential inclusion in the system. Together, these cryptographic primitives

form the backbone of Nescience’s security architecture, ensuring that users can transact and interact privately, securely, and efficiently.

In the following sections, we will explore each of these cryptographic components in detail, beginning with the role of hash functions.

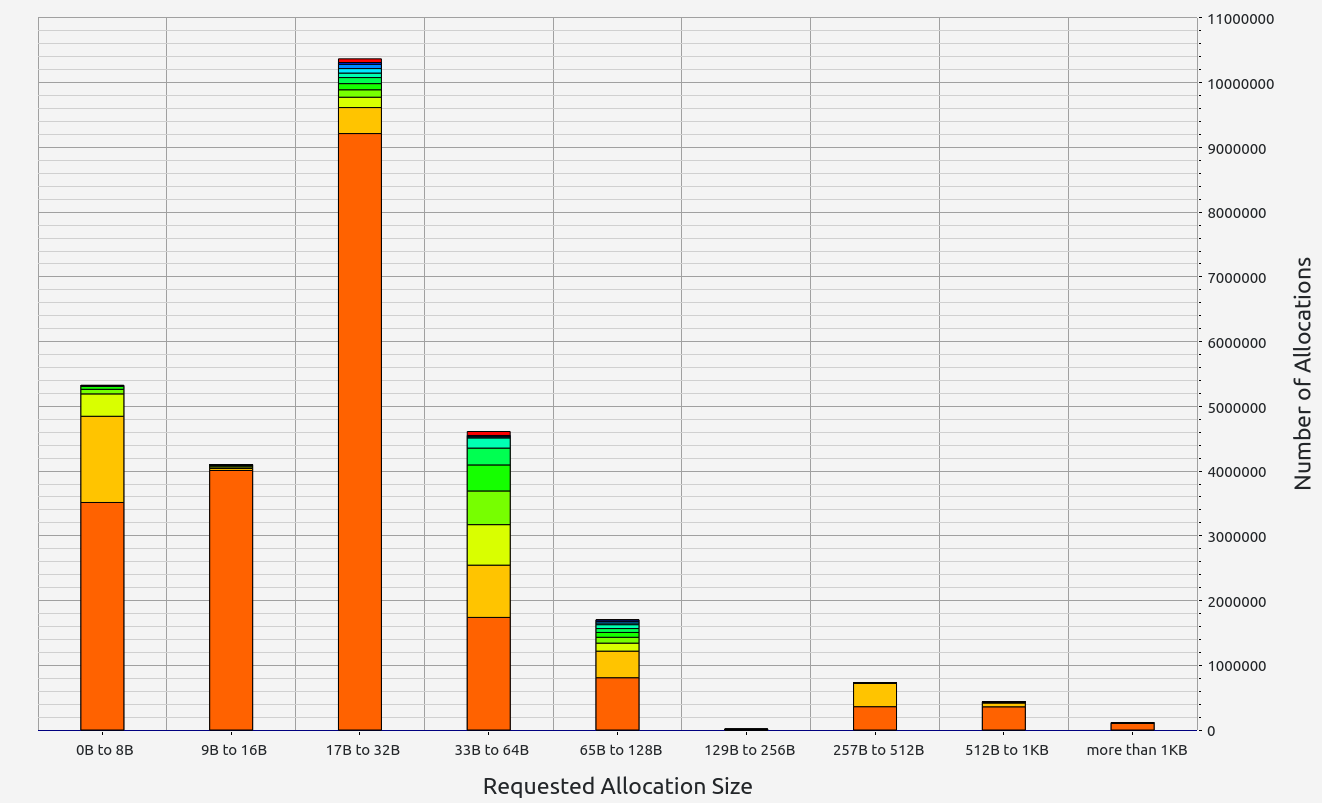

Hash functions are a foundational element of Nescience’s cryptographic framework, serving multiple critical roles that ensure the security, privacy, and efficiency of the system.

One of the primary uses of hash functions in Nescience is to conceal sensitive details of UTXOs by converting them into fixed-size hashes. This process allows UTXO details

to remain private, ensuring that sensitive information is not directly exposed on the blockchain, while still enabling their existence and integrity to be verified. Hashing

the UTXO details allows the actual data to remain confidential, with the hashes stored in a global tree structure for efficient management and retrieval.

Additionally, hash functions are essential for generating nullifiers, which play a crucial role in preventing double spending. Nullifiers are created by hashing UTXOs

and are used to mark them as spent, ensuring that they cannot be reused in subsequent transactions. These nullifiers are stored in a nullifier tree, and each transaction

must prove that its UTXO’s nullifier is not already present in the tree before it can be processed. This ensures that the UTXO has not been spent before, maintaining the

integrity of the transaction process.

Hash functions are also vital in the construction of sparse Merkle trees, which provide an efficient and secure method for verifying data within the blockchain.

Sparse Merkle trees enable quick and reliable proofs of membership and non-membership, making them essential for verifying both UTXOs and nullifiers. By using hash functions

to build these trees, Nescience can ensure the integrity of the data, as any tampering with the data would result in a change in the hash, making the manipulation detectable.

Another critical consideration in Nescience is the compatibility of hash functions with ZKPs. ZK-friendly hash functions are optimized for efficient

computation within the constraints of ZK circuits, ensuring that they do not become a bottleneck in the proof generation or verification process. These hash functions

maintain strong cryptographic security properties while enabling efficient computations in ZKP systems, which is essential for maintaining privacy and

integrity within the ZK framework.

The primary advantage of using hash functions in Nescience is their ability to ensure that transaction details remain private while still allowing for verification

of their validity. Furthermore, by integrating hash functions into Merkle trees, the blockchain data becomes tamper-proof, enabling quick and efficient verification

processes that uphold the system’s security and privacy standards.

As mentioned in the UTXOs in private executions section, the user broadcasts the encrypted UTXOs to the network, along with a commitment to the output UTXOs

using Pedersen hashes. The Pedersen hash is used to create the UTXO commitment. The Pedersen hash is a homomorphic commitment scheme that allows secure commitments

while maintaining privacy and enabling proofs of correctness in transactions. The commitment formula is as follows:

Commitment=C(UTXO,RCK)=gUTXO⋅hRCK

In this formula, g and h are two generators of a cryptographic group where no known relationship exists between them. This ensures that the commitment is secure

and computationally infeasible to reverse or manipulate without knowing the original UTXO components. The random number RCK adds an additional layer of security

by blinding the UTXO's contents, ensuring that the commitment doesn't leak any information about the underlying data.

Importance of homomorphic commitments

It is essential to use a homomorphic commitment like the Pedersen commitment for UTXOs because it allows for the verification of important properties in transactions,

such as ensuring that the total input value of a transaction equals the total output value. This balance is crucial for preventing the unauthorized creation of funds or d

discrepancies in transactions. A homomorphic commitment enables these proofs because of its additive properties. Specifically, the exponents in the commitment formula are additive,

meaning that commitments can be combined and verified without revealing the individual components. For instance, if you have two UTXOs with commitments C(UTXO1,RCK1)

and C(UTXO2,RCK2), you can combine them and verify that the resulting commitment is valid without exposing the actual amounts.

This capability is leveraged through a modified version of the Schnorr protocol, which is used in conjunction with the Pedersen hash to verify the correctness of transactions.

The Schnorr protocol allows users to prove, without revealing the actual values, that the sum of inputs equals the sum of outputs, ensuring that no funds are created or lost in the transaction.

Limitations of standard cryptographic hashes

Standard cryptographic hash functions, such as SHA-256, are not suitable for this purpose because they lack the algebraic structure needed for homomorphic properties.

In particular, while SHA-256 provides strong security for general hashing purposes, it does not allow the additive properties that are required to perform the type of

ZKPs used in Nescience for UTXO commitments. This is why the Pedersen hash is preferred, as it enables the secure and private execution of transactions

while allowing for balance verification and other critical proofs.

Conclusion

By using homomorphic commitments like the Pedersen hash, NSSA ensures that UTXOs can be securely committed and validated without exposing sensitive information.

The random component (RCK) adds an additional layer of security, and the additive properties of the Pedersen commitment enable powerful ZKPs that maintain the

integrity of the system.

NSSA utilizes different cryptographic schemes, such as public key encryption and digital signatures, to ensure secure private executions through

the exchange of UTXOs. These schemes rely on a structured set of cryptographic keys, each serving a specific purpose in maintaining privacy, security, and control over assets.

Here's a breakdown of the keys used in Nescience:

The spending key is the fundamental secret key in NSSA, acting as the primary control mechanism for a user’s UTXOs and other digital assets.

It plays a critical role in the cryptographic security of the system, ensuring that only the rightful owner can authorize and spend their assets.

-

Role of the spending key: The spending key is responsible for generating the user’s private keys, which are used in various cryptographic operations such as

signing transactions and creating commitments. This hierarchical relationship means that the spending key sits at the root of a user’s key structure, safeguarding

access to all associated private keys and, consequently, to the user’s assets. In Nescience’s privacy-focused model, the spending key is never exposed or shared outside

the user’s control. Unlike other keys, it does not interact with the public state, kernel circuits, or even the ZKP system. This isolation ensures that

the spending key remains completely private and inaccessible to external entities. By keeping the spending key separate from the operational aspects of the network,

Nescience minimizes the risk of key leakage or compromise.

-

Generation and security of the spending key: The spending key is generated randomly from the scalar field, a large mathematical space that ensures uniqueness

and cryptographic strength. This randomness is crucial because it prevents attackers from predicting or replicating the key, thereby safeguarding the user’s assets

from unauthorized access: it is computationally infeasible for an attacker to guess or brute-force the key. Once the spending key is generated, it is securely stored

by the user, typically in a hardware wallet or another secure storage mechanism that prevents unauthorized access.

-

Spending UTXOs with the spending key: The spending key’s primary function is to authorize the spending of UTXOs in private transactions. When a user initiates

a transaction, the spending key is used to generate the necessary cryptographic proofs and signatures, ensuring that the transaction is valid and originates from

the rightful owner. However, even though the spending key generates these proofs, it is never directly exposed during the transaction process. Instead, derived

private keys handle the operational aspects while the spending key remains secure in the background. For example, when Alice decides to spend a UTXO in a

private execution, her spending key generates the required private keys that will sign the transaction and ensure its validity. However, the spending key itself

never appears in any public state or transaction data, preserving its confidentiality.

-

Ensuring security through isolation: One of the key security principles of the spending key is its isolation from the network. Since it never interacts with

public-facing elements, such as the public state or kernel circuits, the risk of exposure is significantly reduced. This isolation ensures that even if other parts

of the cryptographic infrastructure are compromised, the spending key remains protected, preventing unauthorized spending of UTXOs.

In summary, the spending key in Nescience is a powerful and carefully guarded element of the cryptographic system. It is the root key from which other private keys

are derived, allowing users to spend their UTXOs securely and privately. Its isolation from the public state and its random generation from a secure scalar field ensures

that the spending key remains protected, making it a cornerstone of security in NSSA.

In Nescience, the private key is an essential cryptographic element responsible for facilitating various secure operations, such as generating commitments and signing

transactions. While the spending key plays a foundational role in safeguarding access to UTXOs and assets, the private keys handle the operational aspects of transactions

and cryptographic proofs. The private key consists of three critical components: privatekey.rsd, privatekey.rcm, and privatekey.sig, each serving a

distinct purpose within the Nescience cryptographic framework.

-

privatekey.rsd (random seed): The random seed (privatekey.rsd) is the first and foundational component of the private key. It is a value randomly chosen from the scalar field, which ensures

its cryptographic security and unpredictability. This seed is generated using a random number generator, making it virtually impossible to predict or replicate.

The random seed is essential because it is used to derive the other two components of the private key. By leveraging a secure random seed, Nescience ensures that

the entire private key structure is rooted in randomness, preventing external entities from guessing or deriving the key through brute-force attacks.

The strength of the random seed ensures the overall security of the private key and, consequently, the integrity of the user's transactions and commitments.

-

privatekey.rcm (random commitment): The random commitment component (privatekey.rcm) is a crucial part of the private key used specifically in the commitment scheme. It acts as a blinding factor,

adding a layer of security to commitments made by the user. The privatekey.rcm value is also drawn from the scalar field and is used to ensure that the commitment

to any UTXO or other sensitive data remains confidential. The commitment scheme in Nescience requires the use of privatekey.rcm to create cryptographic commitments

that bind the user to specific data (such as UTXO details) without revealing the actual data. The role of privatekey.rcm is to ensure that these commitments are

non-malleable and secure, preventing anyone from modifying the committed data without detection. For instance, when Alice commits to a UTXO, privatekey.rcm is used

to generate a Pedersen commitment that ensures the UTXO details are hidden but can still be verified cryptographically. This means that even though the actual UTXO details

are concealed, their existence and integrity can be proven.

-

privatekey.sig (signing key for transactions): The signing key (privatekey.sig) is the third and final component of the private key, used primarily for signing transactions. One possible approach is that

Nescience employs Schnorr signatures, a cryptographic protocol known for its efficiency and security. In this case, the privatekey.sig component would generate

Schnorr signatures that are used to authenticate transactions, ensuring that only the rightful owner of the private key can authorize the spending of UTXOs. Schnorr

signatures are important as they provide a secure and non-repudiable method of verifying that a transaction was initiated by the legitimate owner of the assets.

When Alice signs a transaction using her privatekey.sig, the corresponding public key allows others to verify that the transaction was indeed signed by Alice,

without revealing her private key. This verification process ensures that all transactions are legitimate and prevents unauthorized entities from forging transactions

or spending assets they do not control. Even if an attacker gains access to the signed transaction, they cannot reverse engineer the privatekey.sig, ensuring

the security of Alice's future transactions.

Robustness of private keys in Nescience

Despite the critical role of the private key in the operation of NSSA, the system is designed to maintain security even in the event that the

private key is compromised. This resilience is achieved through the integrity of the spending key, which is never exposed in the process of signing or committing.

The spending key acts as the ultimate safeguard, ensuring that even if a private key component is compromised, the attacker cannot access or spend the user's assets

without control over the spending key.

The architecture’s design, where private keys handle operational tasks but rely on the spending key for ultimate control, ensures a layered approach to security.

This way, the system can mitigate the damage of a compromised private key by maintaining the inviolability of the user's assets.

Conclusion

In summary, the private key in Nescience consists of three interrelated components that together ensure secure transaction signing, commitment creation, and the